Skaters of the high seas

HUANG Danwei (Group Leader, Biological Sciences) September 06, 2021NUS researchers have found that the population histories of three ocean skater species are closely associated with past climatic conditions.

In the placid waters of a pond or pools of a stream you may see long-legged insects running across the water, dimpling the surface but not falling through. These “ocean skaters” or “water striders” are the only group of insects to adapt to life on the open seas. They live by plucking tiny prey trapped at the surface film and manage to keep afloat even when storms lash the ocean surface. The genetics of these ocean skaters captured across the Eastern Pacific Ocean have revealed that their evolution is related to the establishment of the major currents in this part of the world.

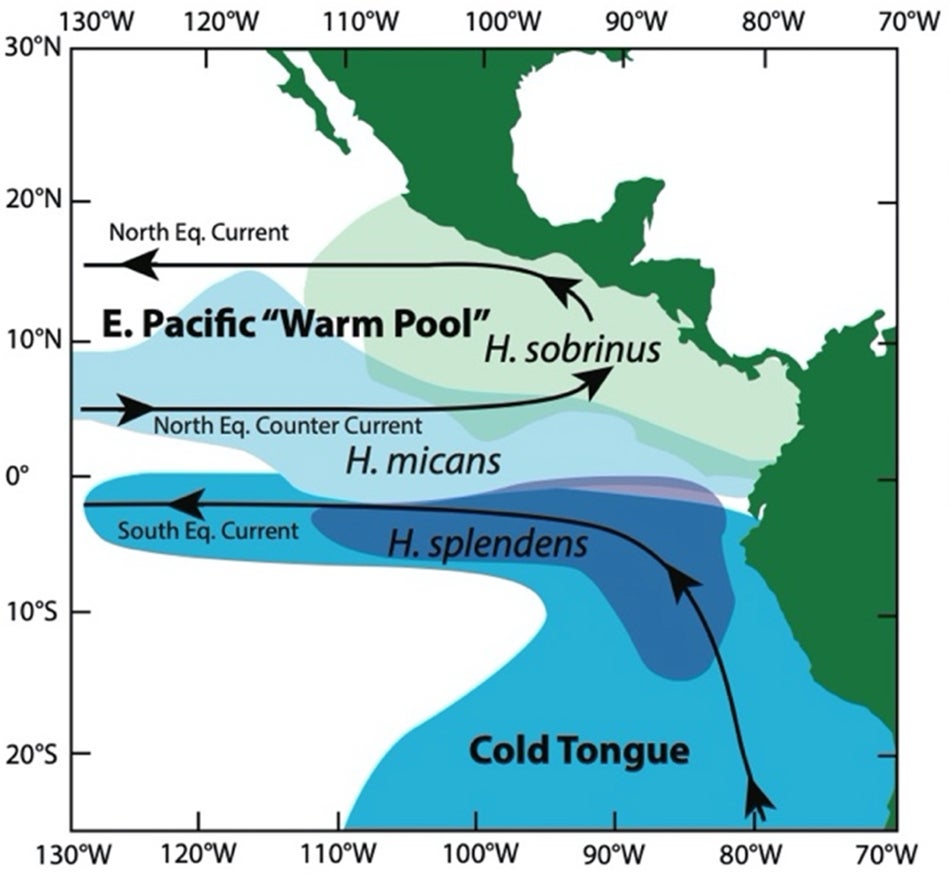

A research team involving Prof HUANG Danwei from the Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore and Dr Wendy WANG from the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum, National University of Singapore identified when and where ocean skaters expanded their populations and established themselves in their current distributions from a genetic study of hundreds of ocean skaters caught in the seas between Peru and Hawaii. The team found a wide variety of genetic variations in each of the three distinct ocean skater species that hinted at their evolution. The oldest species, Halobates splendens, experienced a population expansion nearly a million years ago while the other two younger species, H. micans and H. sobrinus had a population boom about 100,000 to 120,000 years ago. This work was performed in collaboration with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego.

These dates turn out to correspond closely with the increasingly well-resolved record of the ancient ocean climate. Halobates splendens can be found today in the rich, productive waters of the “cold tongue” that originate off the coast of South America which follows the Peru current. Climatological data show that the modern “cold tongue” is only about a million years old and assumed its modern character around the same time when the H. splendens population expanded. The other two species, H. sobrinus and H. micans both diversified in the warm, relatively unproductive waters of Central America. The population of both species expanded when El Niño climate pattern caused warm ocean water to move into the Eastern Pacific Ocean. The El Niño effects were strong in the habitats of both H. micans and H. sobrinus about 100,000 years ago with data showing these species developing their modern genetic patterns and population sizes during this time.

Prof Huang said, “The research findings highlight the deep influence of climatic conditions on marine populations, and help us understand the fates of ocean-dwelling organisms as ongoing climate change accelerates in the coming decades.”

Dr Wang said, “Amazingly, the sea-skater’s genetic history is closely tied to that of our oceans. These remarkable skaters are the only insects to have conquered the oceans where they have thrived for millions of years. They are no strangers to walking on open seas!”

The team is continuing to study the population dynamics of this enigmatic marine animal using genomic tools.

Halobates splendens ocean skater living on the air-sea interface. [Credit: Anthony SMITH]

Map showing the distribution of the three Halobates ocean skater species in the Eastern Pacific Ocean relative to the warm water associated with the El Niño climate and the “cold tongue” off the coast of South America. [Credit: Marine Biology]

Reference

Wang WY*; Chang JJM; Norris R; Huang D; Cheng L, “Distinct population histories among three unique species of oceanic skaters Halobates Eschscholtz, 1822 (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Gerridae) in the Eastern Pacific Ocean”, MARINE BIOLOGY DOI: 10.1007/s00227-021-03944-6. Published: 2021.